Using protein design experiments to guide energy-function development

Why this matters

When a protein is designed on a computer, tiny “impossible overlaps” between atoms can slip into the model. Those clashes may look small on-screen, but they can push a real protein to adopt a different shape than intended. In a December 2025 bioRxiv preprint, the authors show that steric clashing is a systematic bias in a commonly used Rosetta energy function, and they describe how targeted retraining can substantially reduce it.

The challenge

The team set out to understand why experimentally determined structures of designed proteins sometimes differ from their design models. By comparing a large and diverse set of design models to corresponding crystal structures, they looked for recurring failure modes that could explain these mismatches. This analysis pointed to a putative failure mode tied to steric clashing, and also suggested another related to the strength of attractive polar-interaction energies.

The new approach

The paper follows a design-guided workflow: use experimental data from designs to reveal weaknesses in a model, then use a focused benchmark to improve it. To make the clashing problem measurable, the authors relied on an atom-pair distance-distribution benchmark built around relaxing high-resolution crystal structures in Rosetta and checking whether atom-pair distance distributions stay similar before vs. after relaxation. They evaluated performance on a set of 54 structures withheld from training.

They then retrained Rosetta’s Lennard-Jones (van der Waals) parameters using dualOptE, upweighting the atom-pair distribution benchmark to amplify the weak clashing signal. In total, they refit 15 parameters, including the overall repulsive strength (fa_rep) and radii and well depths for the carbon and hydrogen atom types implicated in the clashes. The resulting energy function is named beta_jan25.

Key results

First, the authors show that clashes are not just a design artifact. In their benchmark, structures relaxed with beta_nov16 showed elevated levels of clashing for several atom pairs, many involving at least one carbon atom from a nonpolar sidechain.

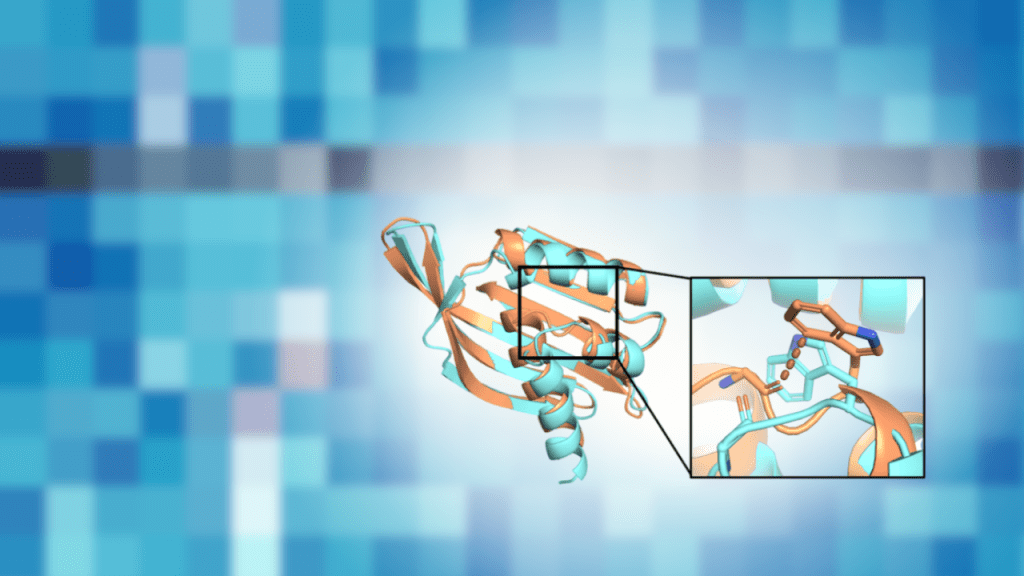

Second, where experimental structures were available, crystal structures tended to be less clashed than the corresponding design models. For carbon–carbon atom pairs from nonpolar sidechains, crystal structures had about 30% fewer clashing atom pairs on average, and reduced clashing was also observed for other atom pairs such as nonpolar sidechain carbon to backbone oxygen. The structural changes that relieved clashes ranged from minor backbone shifts to larger rearrangements that changed the design’s shape.

Third, the retrained model reduced the clashing bias in the benchmark: KL divergence values between “before” and “after” distance distributions moved closer to zero for beta_jan25 compared with beta_nov16, consistent with reduced clashing.

Validation

The study supports its conclusions by (1) systematic comparisons between design models and crystal structures, and (2) benchmark-based evaluation on withheld high-resolution structures, followed by retraining and re-evaluation that specifically targets the clashing signal.

Broader significance

Beyond this specific parameter update, the authors frame the work as a template for “learning from de novo protein design” to improve macromolecular models. They argue that overpacking can be subtle in standard benchmarks, but that amplifying the right signal can be effective, and that similar design-guided approaches could be applied to other modeling frameworks.

A preprint of this work developed by Rocklin, Park, Baker, DiMaio and colleagues recently came out on bioRxiv.